Who defends the defenders? Tropical cyclones pose a risk to the mangroves that protect cities

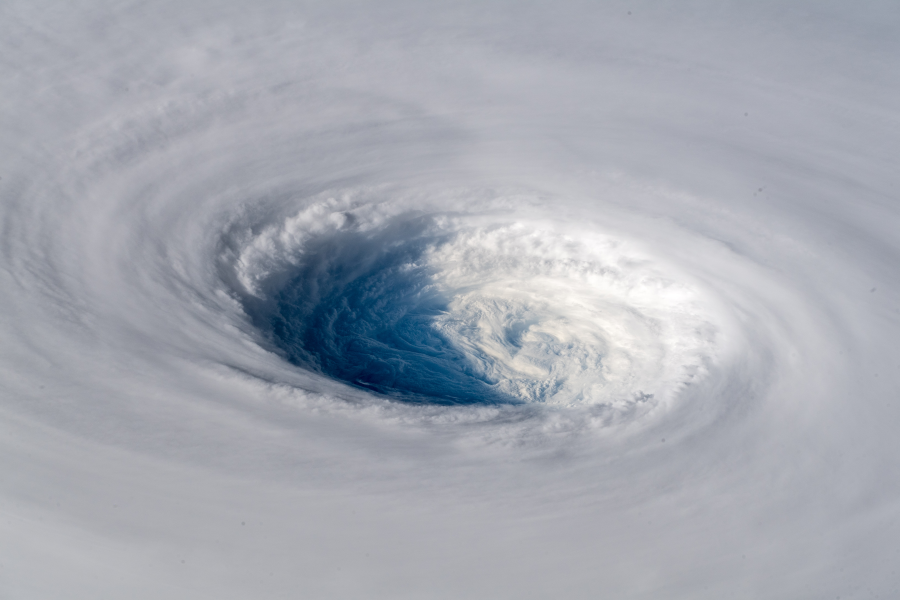

Researchers surprisingly found that the effects of very strong storms on mangroves were only apparent approximately six months after the storm had passed. Credit: ESA/A Gerst/Flickr.com (CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

August 4, 2023

For immediate release

ESA Contact: Alison Mize, gro.asenull@nosila

Author Contact: Yo Mo, ei.dctnull@uyom

Mangroves play a vital role in protecting human habitations from strong storms. But how does that protection affect the mangroves themselves? A team of environmental scientists led by Yu Mo of Trinity College in Dublin harnessed the power of satellites to analyze the damage to mangroves caused by every tropical cyclone around the world since the year 2001. Their results were published in the Ecological Society of America’s journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

“Mangroves are gaining increasing attention as nature-based solutions for protecting cities against storms,” Mo said. “For example, they can mitigate flood risk by reducing storm surge and wave heights. But there is a vital, dynamic relationship between mangroves and storms, a large part of which we’re only beginning to understand. We have a very good record of storm information and observations of the Earth acquired by satellites over the past few decades. Using these records, we were able to look at the global scale for a more comprehensive understanding.”

“Mangroves are really resilient,” Mo said. “Like forest ecosystems that are adapted to forest fires, mangroves are adapted to periodic storm disturbance. It’s only really strong storms that have substantial effects.” The team found that only very strong storms, typically category 3 to 5, significantly affected mangrove ecosystems. More surprisingly, they found that most of that damage was only apparent approximately six months after the storm had passed.

When news crews, non-profits and presidents visit areas hit by cyclones, they tend to land in the immediate wake of the storm. Debris, broken branches and uprooting trees are the most noticeable effects of a cyclone. But, Mo explains, other effects are less easy to see up close.

The influx of floodwaters and sediments, for example, affects hydrological and biogeochemical processes, leading to changes in salinity and prolonging inundation. These changes can affect plants, leading to mangrove diebacks – but they take time to set in, accounting for the six-month lag in effects after a storm has passed.

Her team analyzed the “surface reflectance [of sunlight]” from the mangrove systems captured by satellites, as a proxy of the ecosystem health. The amount of light of different wavelengths reflected from an area tells researchers whether it is open water, covered by damage plants, or buffered by healthy plants, which in turn sheds light on how the mangrove has changed before and after storms.

Using the continuous Earth observations collected by satellites, Mo’s team was able to analyze the mangrove systems’ conditions, going back in time to a year before the cyclone hit, and to track them for years after to paint a fuller picture of how the ecosystems response to storms.

“Other studies have looked at how storms affect mangroves based on factors including windspeed when it hit the coast,” Mo said. “For our study, we wanted to look at storm category, which is defined by the fastest windspeeds a storm attains over its lifetime, because we really want to see if we can make some predictions about the future. By using storm categories, we were able to easily integrate our result with climate models to get an idea of what might happen in the future.”

The team combined their results with projections of potential changes in storm activities in a warmer climate. They found that many mangrove systems may be hit by fewer storms in the future, but that the storms will be fiercer.

Understanding how these strong cyclones affect mangroves will help urban planners and scientists understand how human activities, like the building of dams or roads, may affect the mangroves’ response to storms.

“Mangroves are, in many places, a line of defense people rely upon,” Mo said. “We need to protect the mangroves, but to do that, we need to understand how they respond to and recover from storm damage. When a storm happens, or when anything changes the mangroves, and you want to see how damaged it is, you don’t just go right after the storm, you have to look a few months after as well.”

###

The Ecological Society of America, founded in 1915, is the world’s largest community of professional ecologists and a trusted source of ecological knowledge, committed to advancing the understanding of life on Earth. The 9,000 member Society publishes six journals and a membership bulletin and broadly shares ecological information through policy, media outreach, and education initiatives. The Society’s Annual Meeting attracts 4,000 attendees and features the most recent advances in ecological science. Visit the ESA website at https://www.esa.org.

Follow ESA on social media:

Twitter – @esa_org

Instagram – @ecologicalsociety

Facebook – @esa.org