Wintering pythons? Unlikely, but not impossible

This post contributed by Terence Houston, ESA Science Policy Analyst

A commonly held sentiment is that cold winters prevent established non-native constrictors like the Burmese python in southern Florida from extending north. However, a recent report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service suggests that adaptability may eventually punch a hole in this notion.

A commonly held sentiment is that cold winters prevent established non-native constrictors like the Burmese python in southern Florida from extending north. However, a recent report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service suggests that adaptability may eventually punch a hole in this notion.

The FWS report studied the impacts of the January 2010 winter on the Burmese python and found that, while the severe cold temperatures caused a decline in populations, the non-native python species also exhibited signs of adaptability. The report also highlights a study that observed ten radio-tracked pythons. Nine of the ten snakes died, but the study authors also observed non-radio-tracked snakes using underground burrows, deep water in canals, or similar micro-habitats micro-habitat features of the landscape to sustain themselves.

The FWS report also references another study conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in collaboration with Florida scientists that focused on the 2010 winter. The study was quick to note that that particular winter was unusually cold and severe, leading scientists to conclude a number of factors may have been at play. “It is unclear whether python mortality was exacerbated by the duration of the cold event, the extremely cold temperatures at the end of the period, the sequence of events including a long persistent rain prior to plunging temperatures, or some combination of these factors.”

It is worth noting that in the mountainous portion of their native range in Southeast Asia, Burmese pythons do experience cold winters and have been known to hibernate. It has been speculated that only certain northern populations of Burmese pythons are cold-adapted and that these have not yet found their way into the pet trade.

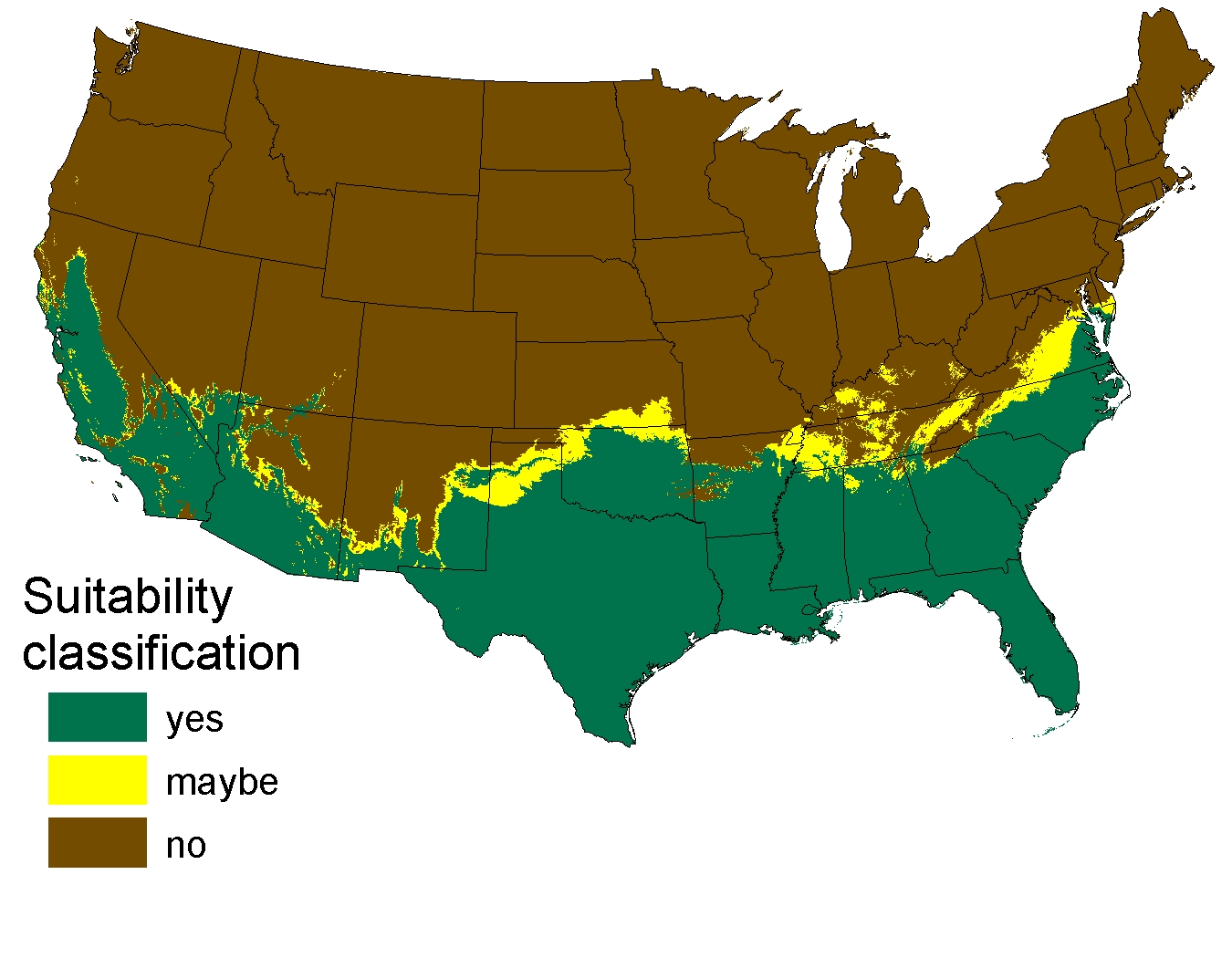

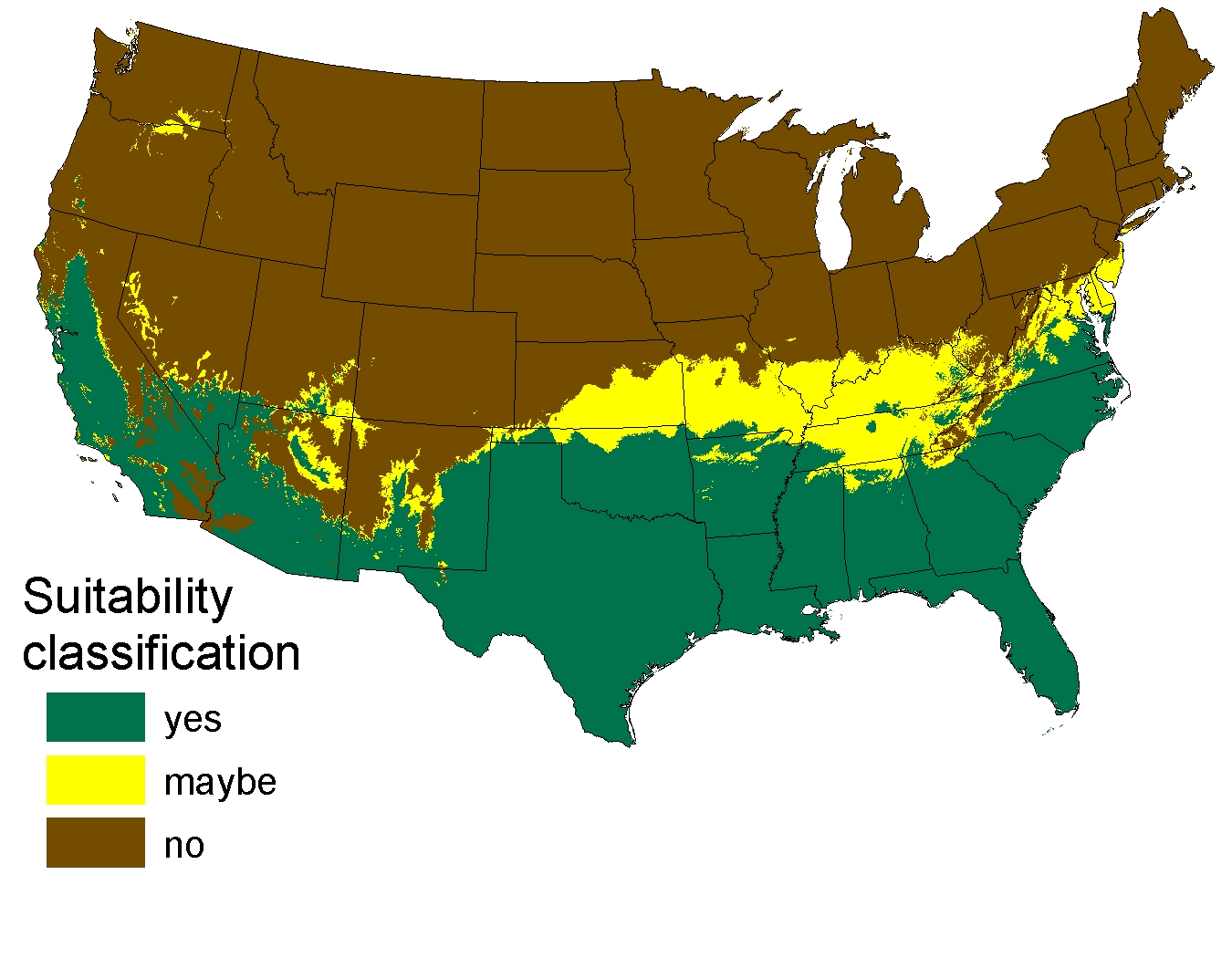

The FWS report concludes: “Given the climate flexibility exhibited by the Burmese python in its native range (as analyzed through the U.S. Geological Survey’s climate-matching predictions in the United States), new generations within the leading edge of the population’s nonnative range could become increasingly adaptable and able to expand to colder climates.”

While doomsday scenarios of pythons spreading as far north as South Carolina currently appear far-fetched, scientists would note that a wild animal’s natural adaptability mechanisms over time should not be underestimated. Consistently warmer winters brought on by climate change would also greatly aid in the establishment of the Burmese python and other non-native constrictors.

Wintering pythons in the U.S. sounds like science fiction now, but every day we are learning that various aspects of science fiction are quickly becoming science facts-of-life.

Photo Credit: William Warby