Mangy wolves suffer hefty calorie drain on cold, windy winter nights

An unwelcome dieting plan: severe mange infection could increase a wolf’s body heat loss by around 1240 to 2850 calories per night, which is roughly 60-80 percent of the average wolf’s daily caloric needs.

During winter, wolves infected with mange can suffer a substantial amount of heat loss compared to those without the disease, according to a study by the U.S. Geological Survey and its partners, published as an Accepted Article (preprint release of the accepted manuscipt) yesterday in ESA’s journal Ecology.

The lost calories equal about two to four extra pounds of elk meat per day, said lead author Paul Cross.

“By definition, parasites drain energy from their hosts. In this study we estimated just one portion of the energetic costs of infection,” said Cross. “Even when parasites do not kill their hosts they are affecting the energy demands of their hosts, which could alter consumption rates, food web dynamics, predator-prey interactions and scavenger communities.”

Sarcoptic mange, present in one of 10 known packs in Yellowstone as of 2015, is a skin disease caused by a mite that burrows into the skin, causing irritation and scratching that then leads to hair loss. In the early 1900s, the Montana state wildlife veterinarian introduced mange to the Northern Rockies in an attempt to help eradicate local wolf and coyote populations.

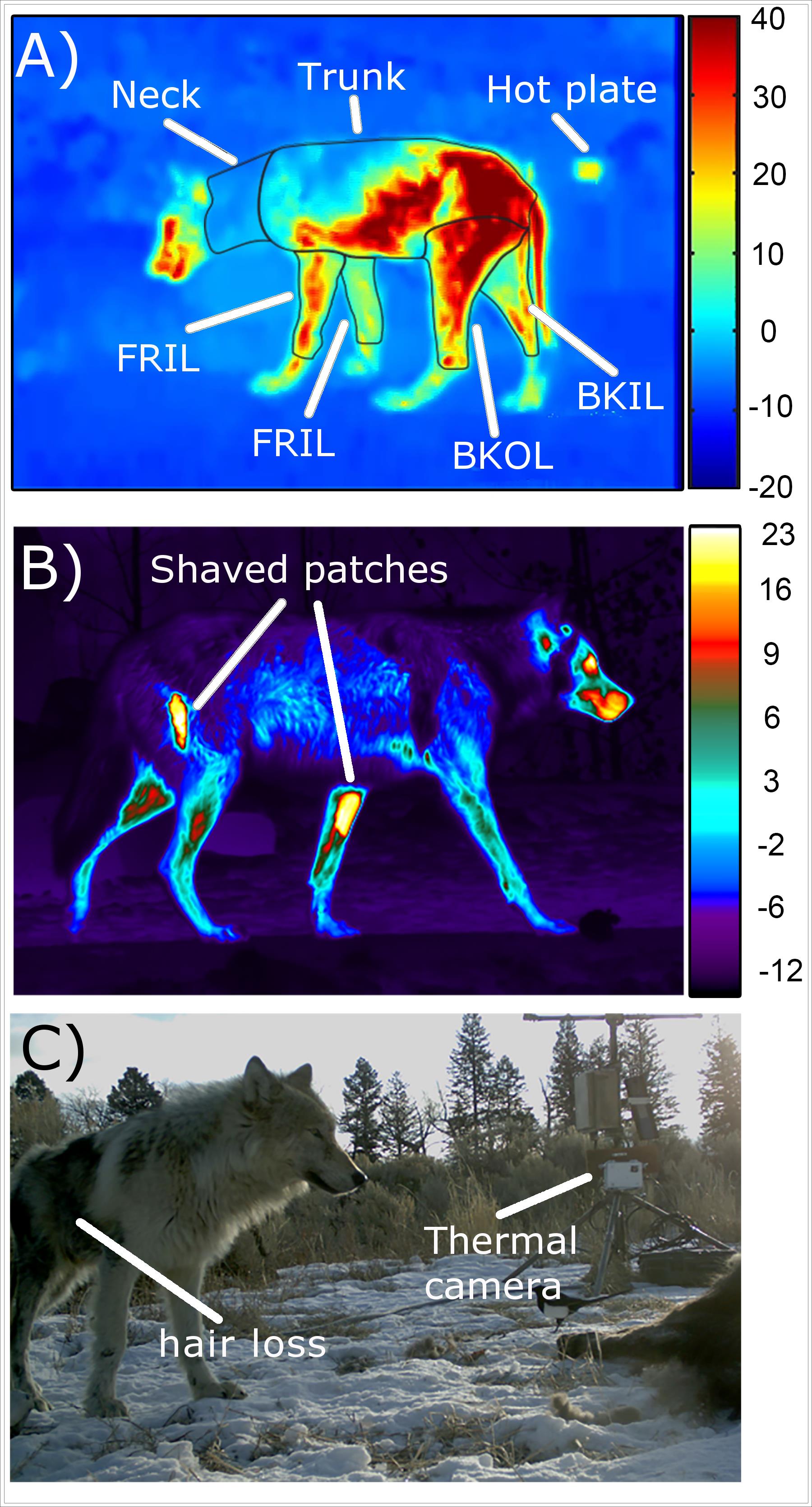

Using a remotely triggered thermal camera to capture vivid and colorful images, Cross and colleagues gathered body temperature data from mange-infected gray wolves in Yellowstone National Park and compared that to a sample group of healthy captive wolves with shaved patches of fur to simulate mange-induced hair loss. Using these data, they quantified the level of heat loss, or energetic costs, during the winter months.

Read a summary of the research from the USGS or check out the research article:

Cross, P., Almberg, E., Haase, C., Hudson, P., Maloney, S., Metz, M., Munn, A., Nugent, P., Putzeys, O., Stahler, D., Stewart, A. and Smith, D. (2016), Energetic costs of mange in wolves estimated from infrared thermography. Ecology. Accepted Author Manuscript. doi:10.1890/15-1346.1

A red glow of escaping body heat glares through thin fur coats in thermal imagery of field (A) and captive (B) wolves, both infected with mange. Shaved patches on the captive wolf replicate the loss of fur from mange. The fur will eventually grow back. (FROL = front outer leg, FRIL = front inner leg, BKOL = back outer leg, BKIL = back inner leg) The remotely triggered thermal camera and weather station are shown in (C). USGS scientists are examining thermal imagery of wolves as one step in assessing impacts of sarcoptic mange on the survival, reproduction and social behavior of this species in Yellowstone National Park. All research animals are handled by following the specific requirements of USGS Animal Care and Use policies. From Cross et al (2016) Fig. 1.