Ecological wild cards of Arizona’s Wallow wildfire

Is a specific person to blame for recent wildfires? While Arizona’s Wallow Fire fuels finger pointing, it takes more than a campfire to fuel the destructive wildfire raging across southeastern Arizona. A perfect storm of local ecology, climate and human management decisions have combined to set the stage for the largest wildland fire in Arizona’s history.

The Wallow Fire that began on May 8 still rages through the largest ponderosa pine forest on the continent. Pinus ponderosa forests cover the higher mesas and mountains of the Colorado plateau on which the northeastern half of the state of Arizona sits. Forest fires are common in ponderosa forests: Typical ponderosa forest climate includes a spring dry season accompanied by increasing air temperatures, low humidity and consistent winds; conditions conducive to frequent early-summer fires.

Before people started suppressing ponderosa forest fires, they burned about every 2-12 years. These were mostly low-intensity ground fires that destroyed small trees and shrubs. This process actually helped to return nutrients to the soil. Mature pines with their thick bark could withstand these small fires, which effectively removed fuel that might have fed larger, more destructive crown fires—fires like Wallow that burn from treetop to treetop.

Then in 1886, the United States government kick-started federal forest fire policy in the newly-created National Parks. Lacking the ecological research to understand the important role of fire in these forests, the US Federal Government embarked on nearly a century of poor fire management policies.

From 1886 to the 1960s, with few exceptions, federal forest fire policy was dominated by fire suppression, according to a comprehensive overview of US Federal Fire policy published in Ecological Applications in 2005. While the first prescribed burn program started in 1968, it was not until 1995 that federal fire policy was altered to “recognize and embrace the role of fire as an essential ecological process.”

During the long period of fire suppression, some forests missed 8 to 10 fire rotations. These rotations had previously created a landscape of “majestic, open stands with rich grasses and occasional shrubs beneath,” as described by early explorers of the western US. Today the landscape is transformed into a dense forest with thickly arranged trees and an accumulation of litter and shrubs. “Where we once had 10 to 25 trees per acre [in western forests],” said Wally Covington, a professor of forest ecology at Northern Arizona University and executive director of NAU’s Ecological Restoration Institute, “we now have hundreds.” While crown fires occurred in ponderosa forests before EuroAmerican settlement, according to a 2003 Ecological Monographs article, crown fires of such intensity as the Wallow fire seem to be a modern product of this forest density.

Despite new fire policies that over a decade ago promised that fire as a “critical natural process” would be integrated into land and resource management plans, a number of factors have stood in the way of progress. “[C]onstraints on smoke production; difficulties in plan preparation; regulatory review; potential impacts on sensitive, threatened, and endangered species; and budgetary procedures,” according to the Ecological Applications article, not to mention the dramatic increase of people and property in the Wildland-Urban Interface, have all delayed fuels-management projects.

Moreover, prescribed burns, a necessary element of a successful fire management program, are risky business for fire managers. If a prescribed fire were to rage out of control, despite proper planning and execution, fire managers could be held professionally and personally responsible. There are also few incentives for those who create proactive and effective fire reduction programs using prescribed burns.

The risks associated with prescribed burns are compounded by the fact that it has become harder to predict where forest fires will go. Before fire suppression, pine forest fires were somewhat consistent, their predictability established by years of evolution and natural processes. Today however, land managers and scientists are not able to confidently predict what direction ponderosa forest fires might take.

This concern about wildfire unpredictability is even stronger as the climate changes. The timing of ponderosa forest fires is determined largely by climate. Alterations in climate patterns, such as the timing of seasonal rains and lightning strikes that come with them, will be important wild cards when it comes to wildfires of the future.

On June 15, 2011, the Wallow Fire became Arizona’s largest wildfire in history. Close to 10,000 people have been evacuated, 32 homes and 36 outbuildings including sheds and barns have been destroyed, more than 469,000 acres of forests destroyed and nearly 5,000 firefighters from across the nation are engaged in a battle with the blaze. According to an International Business Times update on June 15, firefighters believe the Wallow could continue to burn for another few weeks.

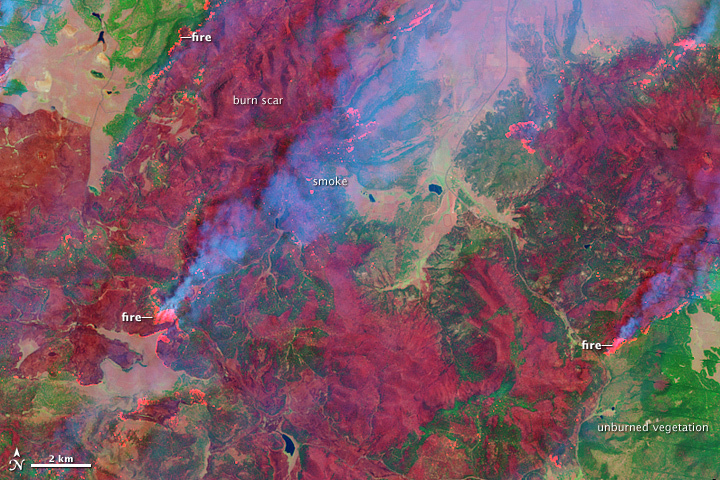

Photo Credit: NASA Earth Observatory