Hi everyone! My name is Vida Svahnstrom and I am a SIP Fellow at Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park this summer. I have lived (and botanized) in as diverse places as Sweden, Florida, Scotland, and Australia, but have never stepped foot in Maryland or indeed the Mid-Atlantic region before. So what brought me here? I am fascinated by rare and threatened plants, and passionate about research which contributes to their continued survival on a rapidly changing planet. Few national parks are home to the number of imperiled plant species as C&O Canal NHP, so naturally, I was ecstatic to be offered the opportunity to relocate to Maryland this summer to work with them!

For anyone reading this that is familiar with the C&O Canal National Historical Park, you might be surprised to learn that the park is home to an astounding 189 plant species that are rare, threatened, or endangered in the state of Maryland. For those of you who haven’t heard of the park, I say this because the park is better known to most for its historical value and recreation opportunities than its biological diversity. The park preserves the history of the C&O Canal which operated for nearly 100 years along the Potomac River, and the park extends 184.5 miles along the river and canal all the way from Cumberland in western Maryland to Georgetown in Washington D.C. The extraordinary length of this park, hugging what has been called the “wildest urban river”, means that it contains a wide range of habitats from Appalachian shale barrens in the northwest, to extensive floodplains further south.

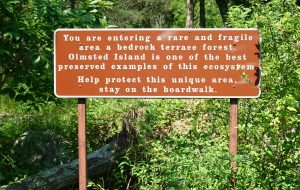

One of the most unique features of the park, both geologically and botanically, is the 15 mile long Potomac Gorge. Thanks to periodic flooding, rare habitats like bedrock terraces, scour bars, and riverside prairies can persist and contain unusual assemblages of plants, often containing species more common in other parts of the country such as the Midwest. These habitats are a hotbed of rare, threatened, and endangered (RTE) species which can only gain a foothold thanks to the unique conditions of the Gorge.

Unfortunately, many of these plants are facing one or more threats, often linked to the ever increasing urban development in this region. These threats include loss of habitat adjacent to the park, competition from invasive species, changes to the hydrology of the Potomac River, and browsing by an overabundance of deer.

My project at C&O Canal focuses on gathering and synthesizing research and other data on RTE species in the park in order to develop species-specific action plans, to ensure their continued survival in the park. For the next twelve weeks, I will be studying many of the park’s species of concern in intimate detail, through a combination of an exhaustive literature review and site visits within the park. This will allow us to make informed decisions on the best course of action for each individual species. This is important because threatened species, even if they occupy similar habitats, can differ in their ecology, growth requirements, genetic diversity, and many other characteristics which will influence how they respond to threats, and, ultimately, how best to manage their populations.

One of the most exciting aspects of this project is a collaboration with the Mt. Cuba Center, a botanic garden in Delaware which has a strong focus on native plants and their conservation. Through this partnership, the park will be developing reintroduction programs for some of the most threatened plant species in the park. Reintroductions can be a highly effective means of improving the prospects of a species’ continued survival, but not all plant species are well suited for reintroduction projects. For instance, they might be extremely difficult to propagate, or there might not be any suitable sites to introduce transplants to. My research will therefore also provide the park and its partners at Mt. Cuba Center with a list of RTE species which could be suitable candidates for reintroduction, and detailed information about how to propagate them ex situ.

Stay tuned for future blog posts from me, and follow me on Instagram @vidasplants! Next time I’m looking forward to sharing more about some of the fascinating plant species I get to work with this summer, and my experiences exploring, living, and working in the beautiful C&O Canal NHP.