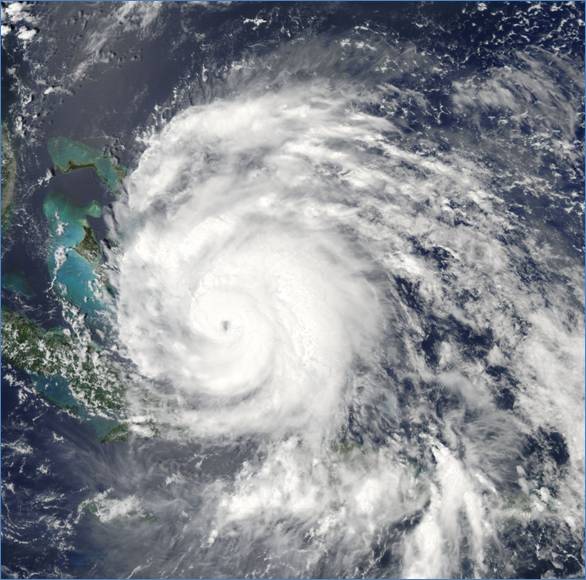

Agency scientific data pivotal in hurricane monitoring efforts

This post contributed by Terence Houston, ESA Science Policy Analyst

When a hurricane strikes, United States federal agency scientists and engineers are among the first on the scene. Such was the case recently, when Hurricane Irene made its way through the East Coast of the United States.

For most residents of the Washington, DC region, the impact was little different than that of a severe thunderstorm. Patios and parking lots were scattered with branches and leaves. A few less sturdy trees fell, all from the pressure of the heavy winds. Hundreds of thousands were left without power in the DC area as were millions more along the east coast.

The first pre-emptive warning signs of a hurricane are detected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Weather Service’s hydrology program, which monitors water levels in our nation’s waterways and issues forecasts and warnings to alert surrounding communities of incoming natural disasters. A major component of the hydrology program is a network of 13 River Forecast Centers around the country. These centers provide hydrologic information to meteorologists, policy-makers and water resource managers to inform response efforts in their local communities. These disaster response efforts are coordinated at the federal level by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

In advance of Hurricane Irene, United States Geological Survey (USGS) scientists deployed sensors along the eastern seaboard to detect “storm surges,” increases in ocean water levels generated at sea by extreme storms that can have devastating coastal impacts. In total, over 260 emergency sensors that measure storm surge were installed in critical areas from North Carolina to Maine. The data that the sensors produce will help define the depth and duration of overland storm-surge, as well as the time of its arrival and retreat. The storm surge sensors were installed on bridges, piers and other structures likely to weather the impact of a hurricane.

Data collected by the sensors will ultimately be used to assess storm damage from winds and flooding, develop better land use and building codes, improve computer modeling used to forecast floods as well as improve public safety protocols. USGS scientists are also assessing landslide potential for areas where Hurricane Irene dumped significant rain.

While much media attention focuses on impacts to coastal areas, inland flooding from rivers and streams has taken a major toll, particularly in parts of Vermont, New Hampshire and New Jersey. According to NOAA, more than 60 percent of U.S. hurricane deaths from 1970-1999 occurred inland, with more than half of tropical hurricane deaths related to freshwater flooding. Information on flood management activities within USGS can be found in a recent EcoTone post.

The USGS also operates an extensive nationwide network with more than 7,000 streamgages that provides up-to-the-minute data essential in issuing flood warnings and community evacuations. This real-time water data from the streamgage network is routinely transmitted to NOAA’s GOES satellite. The satellite relays the transmissions to various satellite downlinks, where it is used by NOAA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, among other federal, state and local agencies.

Additionally, USGS is responsible for taking water quality samples in coastal and inland waterways along the Atlantic to monitor concentrations of nutrients, sediment, carbon, E. coli, and pesticides, which increase with runoff from flooding. These greater concentrations can pose a significant problem for area water managers as they lead to the proliferation of algal blooms. Algal blooms raise the costs of treating drinking water and limit recreational and commercial activities in the affected region at the expense of local economies and businesses, including the fishing industry.

While federal agency officials have continued to request investments in weather monitoring technologies, austerity arguments have taken precedent this year. Natural disasters, including Hurricane Katrina, have traditionally earned bipartisan support from Congress and the Executive Branch for emergency federal funding to aid in relief efforts. Not so today. House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-VA), whose congressional district was coincidentally at the epicenter of the recent East Coast earthquake, recently stated that any federal dollars for hurricane relief should be offset by reductions in spending elsewhere. The statement garnered a sharp rebuke from the White House.

It remains to be seen whether other Congressional Republicans will embrace Cantor’s stance, given that the dollar cost of clean up is expected to number in the billions. FEMA is still estimating the damages associated with Hurricane Irene, but early estimates are in the $6-8 billion range. In comparison, the recent flooding across the Midwest is estimated at $2 billion.

The successful coordinated monitoring and response efforts between local governments and federal agencies, namely the aforementioned, USGS, NOAA and FEMA, undoubtedly saved countless lives and underscores the importance of preserving these agencies’ capacity to do their job.

Photo Credit: NASA