Researchers Find Flaws in Popular Theory on Women’s Math Performance

This post contributed by Celia Smith, ESA Education Programs Coordinator

In science, neat and tidy explanations rarely tell the whole story, and that is exactly what researchers at the University of Missouri have found about stereotype threat theory in their paper on the subject, currently in press at the Review of General Psychology.

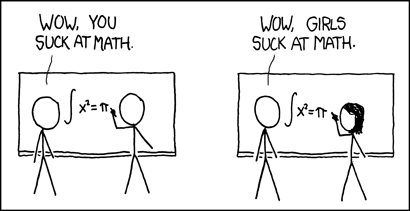

Though it may sound like psychological jargon, stereotype threat is a popular theory with policymakers and the media and is also expressed more idiomatically as the ‘self-fulfilling prophecy.’ Since the theory was first described in a 1999 a Journal of Experimental Social Psychology paper, one of its most popular applications has been to explain why women have lower rates of achievement in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) than men. Supposedly, girls grow up believing that boys are better at math, and belief in this stereotype hampers their performance in math and related fields of science.

Stereotype threat has been widely accepted as a simple and intuitive explanation for the relative lack of high-achieving women in STEM that places blame on social biases rather than flaws in the education system or academia. However, University of Missouri psychology professor David Geary and Gijsbert Stoet of the University of Leeds found that many replications of the original stereotype threat study contained serious flaws in statistical analyses and scientific methodology. Some studies even lacked a control group, meaning they did not compare the experimental effects of stereotyping on women with those on men.

In addition to exposing serious holes in a popular theory, Geary and Stoet’s research highlights a common challenge in problem solving: asking the right questions. U.S. Department of Labor Statistics data show that in 2009, women comprised 29 percent of all environmental scientists and geoscientists, 25 percent of all computer scientists and mathematicians, and just 7 percent of mechanical engineers, indicating a ‘gender gap’ in STEM fields. However, data from the National Center for Education Statistics also show that girls and boys generally leave high school equally well-prepared to study STEM at higher levels. In fact, from 1990-2005, girls earned consistently higher grade point averages than boys in all math and science subjects combined.

These statistics suggest that it is important to distinguish between grades and career success when measuring ‘achievement’ in math and science. The authors of the original stereotype threat study tried to explain the gender gap by suggesting that women performed more poorly on difficult math tests when introduced to a negative stereotype; Geary and Stoet’s research disputes this theory, yet the fact remains that there are still proportionately fewer women with established careers in many STEM fields today. In other words, stereotype threat may have an insignificant effect on women’s higher math performance, but biased social expectations may still influence their career choices.

If this is the case, we may need to use some of the resources currently devoted to reducing stereotype threat to study the personal, financial, and professional incentives and disincentives for women in STEM fields, and identify what is discouraging women from pursuing these careers further despite having the skills to do so (an approach exemplified in this National Research Council report from 2010). Interventions in these areas, either at the collegiate level or in the workplace, are unlikely to be simple or straightforward…but that may be a good indication that we are getting to the bottom of a pervasive societal inequality.

Watch a video of author Gijsbert Stoet of the University of Leeds explaining his latest research on stereotype threat: