Snowflakes still hold mystery

This post contributed by Nadine Lymn, ESA Director of Public Affairs

Their silent, shimmery beauty has long stirred human aesthetic appreciation and for centuries individuals have sought to unravel the secrets of snowflakes. Why are there so many varieties? Why do all snowflakes have six “arms”? And why does each flake appear unique, no matter how many fall from the sky?

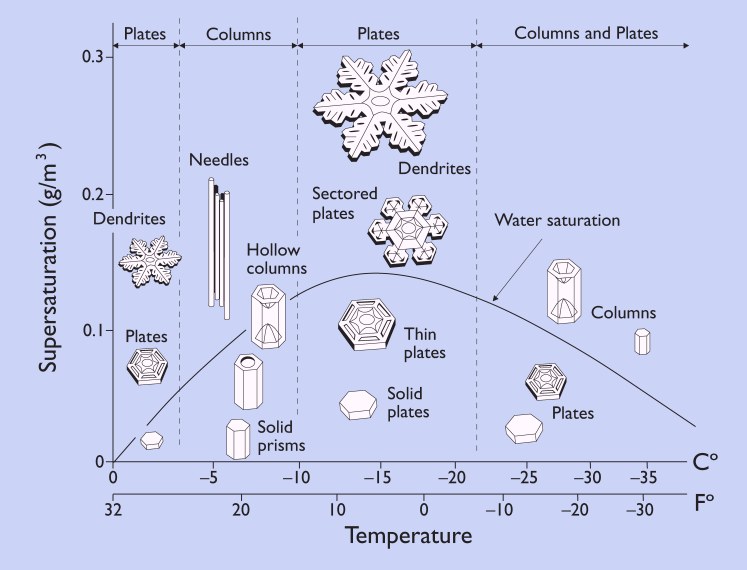

We know the answers to these questions as described on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s website: temperature and humidity determine their shape, their six “arms” are the result of the internal order of an ice crystal’s water molecules, and, because each crystal encounters slightly different atmospheric conditions, each snowflake appears unique.

But enough mystery about the particulars remains that some scientists continue to try to unravel it. One such scientist is Caltech physicist Kenneth Libbrecht, who is looking into the physics of exactly how water vapor molecules are incorporated into a growing ice crystal. He has also created a webpage, SnowCrystals.com which is a true treasure-trove of information for anyone interested in snowflakes. It includes not only magnificent photographs taken by Libbrecht, such as the one below, but also showcases the science of snowflakes and the historical figures who sought to understand these ephemeral beauties.

For example, as long ago as 1611, German mathematician Johannes Kepler, put together a “treatise” for the king which he entitled, A New Year’s Gift or On the Six-Cornered Snowflake. Libbrecht notes that this was the first scientific reference to snow crystals and that Kepler was especially intrigued by the six arms of snowflakes, speculating that it must have something to do with the morphology of the crystals.

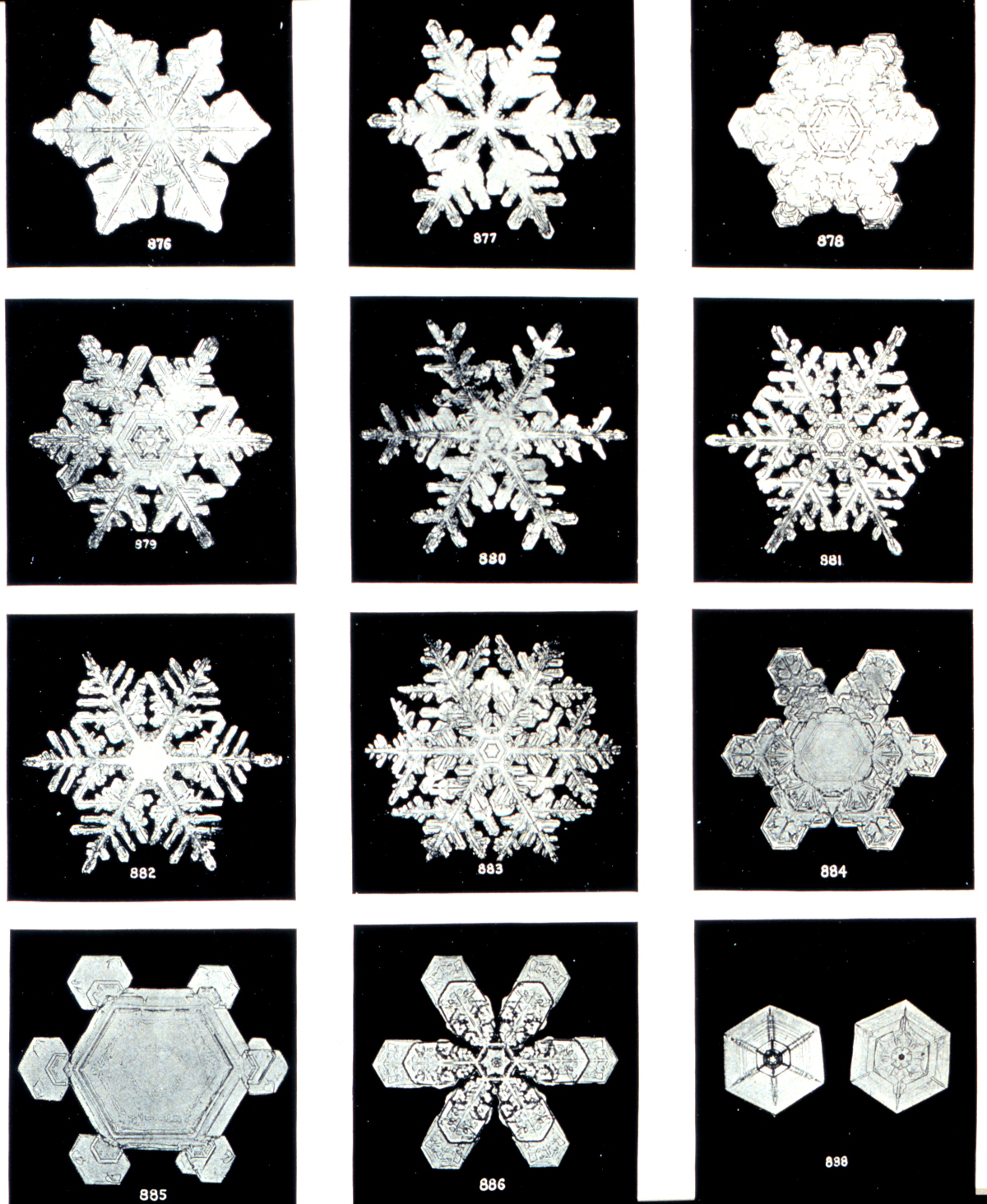

The website includes other individuals, such as “Snowflake Man” Wilson Bentley, a self-educated Vermont farmer, who became so enraptured with snowflakes he saw under his microscope that he persuaded his parents to purchase a special bellows camera to try to capture them before they melted. After years of trial and error, Bentley became the first person to take a photomicrograph of an ice crystal and went on to capture 5,000 images of snowflakes. According to Duncan Blanchard, who wrote a biography about him, Bentley’s first article appeared in Popular Scientific Monthly in 1898 and included this vivid description of an ice crystal:

“A careful study of this internal structure not only reveals new and far greater elegance of form than the simple outlines exhibit, but by means of these wonderfully delicate and exquisite figures much may be learned of the history of each crystal, and the changes through which it has passed in its journey through cloudland. Was ever life history written in more dainty hieroglyphics!”

Part of professor Libbrecht’s research at Caltech focuses on the remaining mystery of why snow crystals change so much with temperature. As seen in the morphology diagram below that Libbrecht has on his website, some generalities are known. For instance, thin plates and stars develop around -2 C (28 F) and columns and slender needle shapes form at around -5 C (23 F). And, drier conditions tend to result in simpler shapes while high humidity drives greater intricacy in crystals.

As Libbrecht and others continue to seek answers to the last mysteries of snowflakes, they simply hold symmetrical beauty for many of us. Although we may not all be quite as enthusiastic as was “Snowflake Man” Bentley, as quoted in Blanchard’s biography:

“…from the very beginning, it was snowflakes that fascinated me most. The farm folks, up in the north country, dread the winter; but I was supremely happy, from the day of the first snowfall—which usually came in November—until the last one, which sometimes came as late as May.”

Credits: Multiple snowflake image, NOAA; morphology diagram, Kepler treatise, Kenneth Libbrecht, SnowCrystals.com