Early career scientists publish earlier: An analysis with Google Scholar

As I was reading through Adam Grant’s recent book Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World, a quote he references by Einstein made me think about the ideas that early career scientists generate: “A person who has not made great contributions to science by the age of 30 will never do so.”

This quote got me thinking about how the landscape of peer-reviewed publishing differs between early career scientists and those in their mid to late careers. As someone that is navigating the tenure and promotion process within a university, we often seek to compare our research productivity and output to others that have recently gone through the process. How many publications did that professor have before receiving tenure? How many citations did she have to her publications?

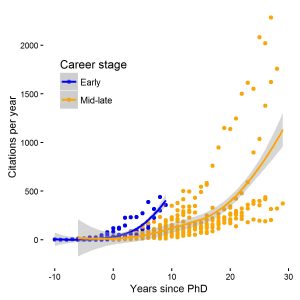

With the numerous citation indexes now available to examine research productivity along with career stage, I set out to attempt to answer the question: How does the number of annual citations to research publications differ between early and mid to late career scientists?

I used data from my own Google Scholar coauthor list to find some answers. I have a total of 11 early career coauthors (defined as receiving their PhD within the last 10 years) and 13 mid to late career coauthors. The coauthors are comprised mostly of university faculty and federal research scientists. The main variables used in the analysis were:

- Career stage (early or mid-late career),

- Year of PhD awarded,

- Number of citations per year to research publications, and

- Number of citations per year before and after the PhD was awarded.

The graph indicates a smoothed regression line by career stage. The general trend shows an increasing number of annual citations for both career stages. But the data for early career scientists is intriguing: early career scientists have publications being cited well before receiving their PhD (up to ten years prior) and have a larger number of citations in the ten years that follow their PhD relative to mid to late career scientists.

Early career scientists receive 35% of their total citations prior to receiving their PhD, compared to 9% for mid to late career scientists. At five years since receiving one’s PhD, early career scientists receive more than double the amount of citations compared to mid and late career scientists.

The differences between the two career stages point out the differences in the landscape of publishing. But in sum, I’m not sure I would subscribe to Einstein’s statement that early career stage scientists run out of all our good ideas when we’re 30. In fact, there may even be a formula that relates age to research productivity: see the Scientists can publish their best work at any age column from Nature that was published late last year.

Matt Russell is an assistant professor and Extension specialist in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Forest Resources. His work can be found at health.forestry.umn.edu.