#MySciComm: You’re gonna need a bigger online outreach strategy: How Dr. David Shiffman uses social media to teach the world about sharks

This week, Dr. David Shiffman responds to the #MySciComm questions!

*Editor’s note: David is available Wednesday, August 29, 2018 (the date of publication) to answer questions you may have about what it’s like to be a science communicator, how he got into it, and sharks, of course! Connect with him in the comments, or on Twitter and Facebook (use #MySciComm so he sees it).

David Shiffman in Miami, Florida, after a shark research trip during his PhD (Photo by Josh Liberman)

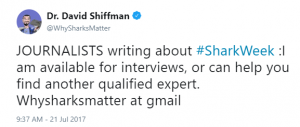

Dr. David Shiffman is a Liber Ero Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Conservation Biology at Simon Fraser University, where he studies the conservation and management of sharks. He has been interviewed for over 200 mainstream media articles, and has bylines with the Washington Post, Scientific American, Slate, Gizmodo, and more. He is also an award-winning public educator who has used social media to answer thousands of people’s questions about sharks, and has taught over 500 scientists how to use social media to communicate their research to the public. Connect with him on twitter @WhySharksMatter and Facebook.

The #MySciComm series features a host of SciComm professionals. We’re looking for more contributors, so please get in touch if you’d like to write a post!

————————-

Okay, David…

1) How did you get into the kind of SciComm that you do?

SHARRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRK!

I’ve loved sharks as long as my family can remember.

But, when most people hear that word, they picture a scene straight out of Jaws. They picture a monster stalking and killing you and your family for no reason except that it’s evil.

In reality, shark bites are incredibly rare—more people are killed by vending machines, or flower pots, or selfie accidents than are killed by sharks. I would have told you that (well, not the part about selfies) when I was seven years old.

As I grew up and learned more and more about sharks, I started also telling people that sharks provide essential ecosystem services that keep food webs in balance. I told people that humans are better off with healthy shark populations off our coasts than we are without them.

And yet, unsustainable overfishing has resulted in 24% of all known species of sharks and their relatives being assessed or estimated as Threatened by the IUCN Red List.

A lifetime of loving sharks and learning about them has taught me that sharks are some of the most misunderstood, some of the most ecologically important, and some of the most threatened animals in the world.

I’ve always wanted to be a shark researcher, but becoming one of the most followed science communicators on the internet was never part of the plan.

My parents have always been very supportive of this obsession of mine, though I believe they suspected I’d grow out of it eventually. Growing up far from the ocean in Pittsburgh, this meant lots of trips to the shark tank at the Pittsburgh Zoo, and it meant reading every shark book I could get my hands on. It even meant watching lots of Shark Week, though I suspect that seven year old me would be shocked to hear me called “Shark Week’s biggest critic”.

As soon as I was old enough, I got SCUBA certified. There’s not a lot of exciting diving in Pittsburgh, so this meant going on lots of awesome family trips to tropical destinations, and it meant spending five summers at marine science and SCUBA summer camp called SeaCamp. I later worked there for two summers, where I taught (you guessed it) shark biology.

I applied to Duke University with an essay focusing on my first time SCUBA diving with sharks, and got to open my essay with,, “don’t worry, dad, they don’t usually eat people.” Later when volunteering as an alumnus at a recruiting event, I heard a Duke Admissions counselor reference my essay as one of her all-time favorites, and she swore that she didn’t know it was mine when she said that. While at Duke, I performed an independent study focusing on stingray feeding behavior in the outer banks.

I later got a Masters in Marine Biology at the College of Charleston, where I studied sandbar sharks (follow #BestShark on twitter to learn why I love these animals so much). During my Ph.D. at the University of Miami, I was awarded the Florida Marine Science Educator of the Year award for my efforts speaking to schools throughout the state about sharks and shark conservation.

Bringing sharks online

In 2008, my former Duke roommate Dr. Andrew Thaler told me about ScienceOnline, a conference focusing exclusively on how scientists can use internet tools to better communicate science with the public. He knew that I loved to talk to people about sharks and correct misunderstandings, and thought that the communications tools he learned about at ScienceOnline would be a great fit for my goals.

When I attended the next ScienceOnline, I met scientists, science educators, and science journalists who used social media and other online tools to reach a larger audience than I ever thought possible, and I was hooked. These tools are AMAZING, and they make it easier than ever before in human history for experts to share their expertise with the interested public, with policymakers, and with journalists. I started my twitter account @WhySharksMatter and started blogging for Southern Fried Science, a blog that Andrew founded that has since become one of the most widely read ocean science blogs on the internet.

I went to five annual ScienceOnline meetings. I started running my own sessions there, and eventually organized ScienceOnline Oceans, an ocean-focused spinoff, in 2013. ScienceOnline has since closed down in some of the early ripples of the #MeToo movement, but I still run OceansOnline, inspired by ScienceOnline Oceans, at the biannual International Marine Conservation Congress.

It’s been nearly a decade since that fateful conversation with Andrew, and I’ve now written hundreds of blog posts for Southern Fried Science, and I’ve tweeted over 200,000 times. I also run professional development training workshops for scientists interested in using social media to communicate their science to the public. Yes, I’m available to teach this to your group. As of summer 2018 I’ve given this training to over 500 scientists.

The single most important lesson that I teach people is that when used properly, social media can be a powerful tool that helps you achieve your communications goals—but “talk about science on social media” is NOT, in of itself, a goal.

And when I say social media, I mostly mean twitter, at least for the purposes of this interview.

My favorite thing to do on twitter is “ask me anything,” a format popularized by Reddit. (I did one on Reddit and made it to the front page a few years ago, but I prefer Twitter’s interface.) If you’re not familiar with this, it’s pretty simple: I identify myself, my area of expertise, note how long I’m available, and invite people to ask me, well, anything! Most of the questions I get are about sharks, but they certainly don’t have to be. I typically do this once a week for an hour, often on the bus ride to work or while sitting at an airport waiting for my next flight. I’ve been having folks ask me anything since 2014, and I’ve gotten to answer thousands of people’s questions.

Twitter is also great for engaging with journalists. Only 24% of US adults have a twitter account, but pretty close to 100% of journalists have a twitter account, and many journalists use the service to find sources of story tips. By putting yourself out there as a credible expert source, you can help make media coverage of your field more accurate. You can also use twitter to correct inaccurate media coverage. When I e-mail journalists to point out factual errors in a story, I get a response about 5-10% of the time, but when I tweet at them I get a response about half the time. (Since media coverage of sharks is…problematic, I always have plenty of work to do).

Being on twitter also allows for research collaborations. There are experts in my field who I’ve never met outside of twitter, but who I consider trusted colleagues or even friends. I even coauthored a paper with people I had only ever met on twitter, one of several peer-reviewed publications I’ve written about social media. You may be the only one in your department with a particular set of research interests, and without twitter you may only get to enthusiastically geek out with others that share those interests once a year at a conference. With twitter, you can chat about the things you’re passionate about every single day. These online communities can be particularly useful for graduate students, early career researchers, or scientists who come from historically underrepresented minority groups.

Even if you never (or rarely) tweet anything yourself, by following the right accounts you can become better informed about your field and other issues that matter to you. I’ve lost count of how many relevant research papers I’ve only come across because a colleague shared them on social media.

I’m fortunate that my fields (marine conservation biology and elasmobranch biology – sharks, rays, etc. –) have long recognized the importance of public outreach to accomplishing our goals.

The communications skills I’ve developed while using social media for public outreach have made me a better writer and a better teacher. The personal and professional relationships I’ve made using social media for public outreach have made me a better collaborator and a better person.

Considering the facts about sharks vs. their stereotypes, studying public perception of sharks and their conservation while using social media to educate people about these amazing animals is a worthy way to spend my professional life.

2) What are your top 3 SciComm tips and/or resources?

1. Don’t be scared of the formatting/mechanics of twitter.

If you can learn your technical research discipline you can certainly learn the difference between a hashtag and a retweet! There are many guides for beginners available, including this one by me.

2. Track down influencers and learn from what they do.

Once you have a twitter account, I recommend tracking down some influencers in your field of interest (scientists, journalists, non-profit employees, etc.) and just watching them for a while. See what types of things they share and what they say about the things they share. See who they talk to and what kind of conversations they have. Ideally, follow enough different people that you’ll get to observe several different strategies and styles to find the one that’s right for you. Once you have a sense of the types of strategies and styles that are possible, try some and see how they work for you!

3. Think about your goals to inform your twitter strategies.

If you want to build a high follower base, there’s no secret formula. You simply share lots of content that people are interested in every day for years. However, consider if you actually need to do that to accomplish your goals. If you only have a few messages a year that you’d like to get to a large audience, you probably don’t need lots of followers. Instead, you can just ask the influencers in your field to retweet your tweets (I’m always happy to do this). Then, you can focus the rest of your time on using twitter in a way that is more aligned to your goals vs investing the time and effort to build a large following just because.

*Editor’s note: David is available Wednesday, August 29, 2018 (the date of publication) to answer questions you may have about what it’s like to be a science communicator, how he got into it, and sharks, of course! Connect with him in the comments, or on Twitter and Facebook (use #MySciComm so he sees it).