Machine learning streamlines detection of African forest elephant vocalizations

A neural network model reduces the amount of audio data requiring human inspection by 98%

July 24, 2020

For Immediate Release

Contact: Heidi Swanson, (202) 833-8773 ext. 211, gro.asenull@idieh

A new artificial intelligence application can pinpoint low-frequency elephant calls buried within vast stores of audio recordings, bypassing the bottlenecks that researchers face when they sort through data by hand. Jonathan Gomes-Selman and Nikita Demir, both recent graduates of Stanford University, trained an artificial neural network to “listen” to audio files and pick out all the sound bites containing the rumblings and grumblings of African forest elephants.

They will present their research (Automatic detection for passive acoustic monitoring of the African elephant) at the Ecological Society of America’s upcoming virtual conference, as part of an on-demand session about methods and tools for working with big data in ecology.

Forest elephants, gorillas and other large mammals congregate in forest clearings known as “bais,” like this one in Central African Republic, part of the Sangha Tri-National Landscape, which also includes portions of Cameroon and the Republic of Congo. Photo courtesy of David Weiner, International Communication and Education Foundation, CC BY-NC 2.0.

Without the aid of automated tools, isolating elephant rumbles from the cacophony of other rainforest sounds is a time-intensive process – and it is a process that Gomes-Selman knows well. While volunteering for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Elephant Listening Project as a high school student in 2013, he was responsible for sifting through recorded audio data and manually identifying the elephant calls. “Moving forward, I always had in the back of my mind the idea that the work I had been doing surely could be automated and knew how powerful such a tool could be,” he says.

Now, Gomes-Selman is following through on this idea. He and Demir developed a neural network model that can automatically identify elephant calls found in audio recordings collected by the Elephant Listening Project, whose autonomous recording devices, placed in elephant habitat across Central Africa, have captured audio data amounting to over a century’s worth of playback time. The lab’s recordings are guiding efforts to combat poaching and other human-induced stressors that threaten the species’ survival and may hold answers to long-pondered mysteries of elephant communication and social behavior.

Much of the data collected by the Elephant Listening Project comes from open forest clearings, called “bais,” where elephants often congregate. But Gomes-Selman and Demir were interested in a setting where elephants’ social behaviors are more shrouded in mystery: the densely vegetated lowland rainforest of Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park. The park, located in the Republic of the Congo’s northern region, consists of nearly a million acres of pristine forest.

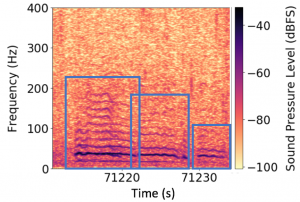

A spectrogram shows a visual representation of an African forest elephant’s rumbles (outlined by blue rectangles). Courtesy of Jonathan Gomes-Selman.

While moving about in lowland rainforest, elephants communicate partially through “rumbles,” a low-frequency, long-range vocalization that is often undetectable to the human ear, but can be picked up by passive audio monitoring devices. And even though deploying the recording devices in such a remote region can require days — or even weeks — of hiking, the devices, once placed, can detect elephant rumbles from within three square kilometers of surrounding forest.

Many conservation crowdsourcing projects have popped up in recent years and provide volunteers with the opportunity to participate in “people-powered” research. But the field of conservation biology is also full of opportunities for computer scientists — or future computer scientists — who want to use their skills and ideas to make conservation efforts more efficient and more effective.

Gomes-Selman plans to continue bridging his interests in conservation and computer science, including specific plans to continue collaborating with the Elephant Listening Project. “Right now we are working primarily on post-processing of data that has been extracted from the field,” he says, “but one ultimate goal is to eventually help design or influence the creation of real-time detectors that can be deployed in the field and transmit real-time data to assist in elephant conservation.”

On-demand session at the 2020 ESA Virtual Annual Meeting:

This contributed talk, “Automatic detection for passive acoustic monitoring of the African elephant,” is part of virtual session all about methods and tools for working with big data in ecology. Other presentations in the session include:

- Establishing monitoring systems for Vietnam’s payments for forest environmental services mechanism — Lauren F. Keller, Truong Le Hieu, Dang Thuy Nga, Le Thanh Binh, and Nguyen Phan Dong, Winrock International

- Assimilation of tree ring and forest inventory data to forecast future growth responses of Pinus ponderosa — Kelly Heilman, University of Arizona; Michael C. Dietze, Boston University; John D. Shaw, USDA Forest Service; R. Justin DeRose, Utah State University; Stefan Klesse, Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL; Andrew O. Finley, Michigan State University; Jacob Aragon, Andrew T. Gray, Alexis H. Arizpe, and Margaret E. K. Evans, University of Arizona

COS 125 – Big Data In Ecology – Methods and Tools 7 — Automatic detection for passive acoustic monitoring of the African elephant

- Jonathan M. Gomes-Selman, Nikita N. Demir, and Andreas Paepcke, Stanford University; Peter Wrege, Cornell University

- Presentation abstract

- Contact: ude.drofnatsnull@8sgj

2020 Virtual Annual Meeting

Harnessing the ecological data revolution

August 3 – 6, 2020

Ecologists from around the world will gather online this August for the 105th Annual Meeting of the Ecological Society of America. The plenary talks and select panels will be aired live with Q&A. Other sessions will be available for viewing on demand with asynchronous Q&A. Presenters also have the option to host a live Q&A with viewers.

The opening plenary will feature Microsoft’s Chief Environmental Officer, Lucas Joppa. He will discuss the advances in computing and data infrastructure that ecologists can use to address the existential challenges of responding to changing climates, ensuring resilient water supplies, sustainably feeding a rapidly growing human population and stemming an ongoing global loss of biodiversity.

Meeting plenaries and symposia will explore the meeting theme “Harnessing the ecological data revolution.” Like many science fields, ecological research is being flooded by diverse and data-rich sources of information, which is opening new avenues of research but also creating new challenges for ecologists. Scientific sessions will explore new and integrative approaches used to understand pressing ecological issues.

ESA invites press and institutional public information officers to attend for free. To apply, please contact ESA Public Information Manager Heidi Swanson directly at gro.asenull@idieh.

###

The Ecological Society of America, founded in 1915, is the world’s largest community of professional ecologists and a trusted source of ecological knowledge, committed to advancing the understanding of life on Earth. The 9,000 member Society publishes five journals and a membership bulletin and broadly shares ecological information through policy, media outreach, and education initiatives. The Society’s Annual Meeting attracts 3,000 – 4,000 attendees and features the most recent advances in ecological science. Visit the ESA website at https://www.esa.org.