Water rises, cattle graze, dunes walk on the Kalahari

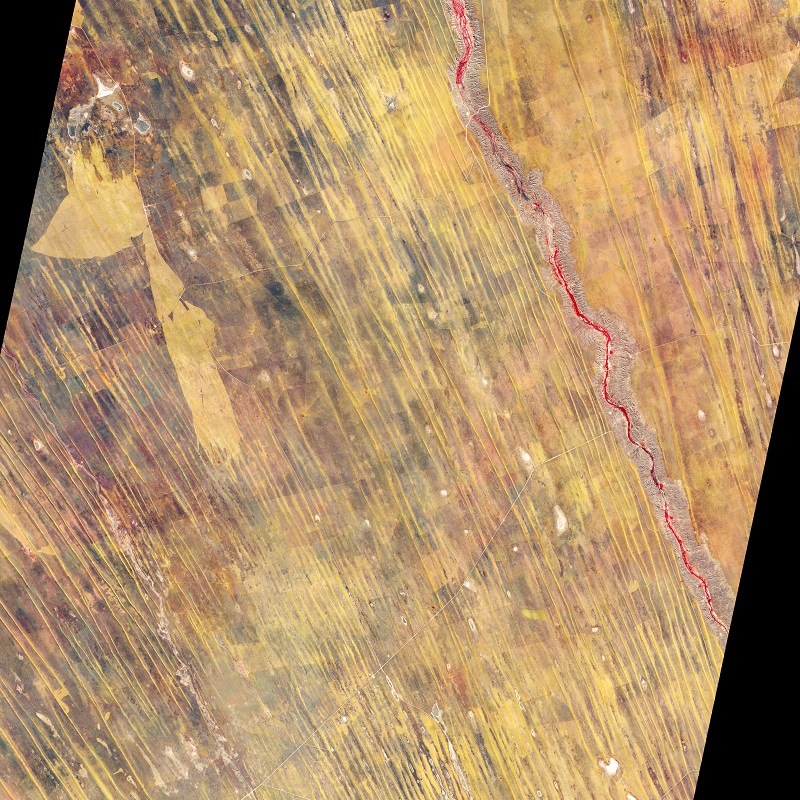

Stable dunes up to 25 meters high run in parallel lines in the southern Kalahari, Namibia, in this image acquired by NASA’s Terra satellite on May 7, 2007. The dunes likely formed between 17,000 and 10,000 years ago. In recent years, grazing cattle have denuded the perennial grasses that grow on the dunes, and the sand is becoming mobile. Credit, NASA.

There is water under the dry sands of the Kalahari. Pumps tap the aquifer, bringing up ancient water to green the sandy savanna and feed cattle. Under the hooves of cattle, long-frozen waves of sand have begun to move, as Abinash Bhattachan and colleagues reported in Ecosphere in January 2014.

The Kalahari, which stretches across much of Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa, is not as dry as the imposing Namib Desert to the west, but Kgala, the “great thirst” to the Tswana people who live there, is a harsh place. A relatively generous 20 inches of rain per year wet its wettest reaches in the north. In the south and west, only 4 – 8 inches of rain bring a brief greening to the dunes. Low, variable winds and a cloak of perennial grasses have held the sand dunes stable for thousands of years. But the dunes have begun to stir.

The cattle have wrought change on the savanna ecosystem of the Kalahari. Grazing cattle leave bare ground and favorable conditions for the invasion of woody shrubs (which the cows can’t eat) and annual grasses (which the cows don’t like). The short roots of grasses that sprout annually from seeds are not as successful at rooting the dunes in place as the deeper roots of perennials. Uncovered, the dunes have awakened and begun to move in the wind.

As the land becomes unwelcoming to cattle, their handlers move to virgin territory, and sink new wells to irrigate the dry land. The boon of the underground water has led to a cycle of land degradation.

The good news, said the authors, is that the dunes may still be returned to their grass-covered slumbers. The tipping point for the dunes is overgrazing that wipes out too many perennial species. If the perennial grasses can recover from rhizomes or from seeds banked in the sandy soil, dunes can stabilize. At Gakhibane, Botswana, near the South African border, the local community set aside a cattle-free zone 15 years ago to slow the walk of a dune. Inside the fence, the grass has regrown, demonstrating a way forward for restoration. But, the authors worry, if the future of the Kalahari is drier, the reactivation of the dunes may become irreversible.

Without grasses to anchor the dunes in place, their sand grains blow in the wind. Credit: Paolo D’Odorico. See more images in the NSF gallery.

Read more about this story in a National Science Foundation Spotlight: “Sleeping sands of the Kalahari awaken after more than 10,000 years.” 8 October 2014.

Resilience and recovery potential of duneland vegetation in the southern Kalahari (2014) Abinash Bhattachan, Paolo D’Odorico, Kebonyethata Dintwe, Gregory S. Okin, and Scott L. Collins. Ecosphere 5:1 art2.