In phenology, timing is everything

— a brief overview of how to study climate change through plant sex, and what to do if your greatest scientific mentor and collaborator dies half a century before you are born.

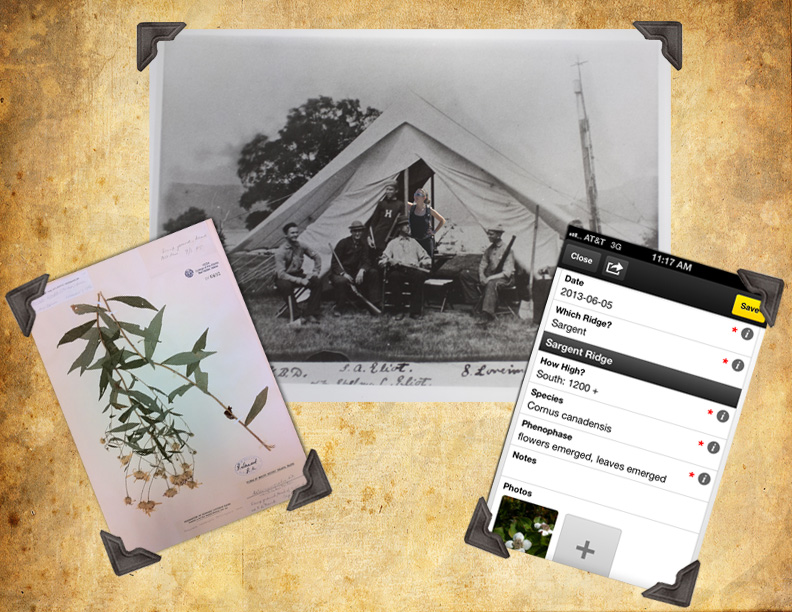

Caitlin McDonough MacKenzie, a PhD candidate in ecology at Boston University, is the runner-up for this year’s Science Cafe Prize. She took a technical topic, made it personal, and bridged history in words and pictures. We liked her image so much that we had to share it with everyone. Meet McDonough MacKenzie and learn more about her “Science in the attic: Long-term spring phenology of trees, wildflowers and birds in Northern Maine building on a forgotten journal” on Wednesday, August 7, during the afternoon poster session (PS 32) in Exhibit Hall B of Minneapolis Convention Center at ESA’s annual meeting.

McDonough MacKenzie was also one of ESA’s Graduate Student Policy Fellows this year. Hear about her experience on the Ecologist Goes to Washington podcast with host Terence Houston.

Same Data, Different Century. Sometimes I believe I was born to be a 19th century naturalist. Compiling long term records of flowering phenology involves stitching together old data (for example, this herbarium specimen from 1895) with new data (a phenology observation collected on a smartphone app in 2013). As I trek across Mount Desert Island in the 21st century, I am keenly aware of the naturalists who came before me; in my mind, I insert myself into the troupe of Harvard boys whose field notes and camp logs have become my baseline data. I really love S. A. Eliot’s sweater. Caption, Caitlin McDonough MacKenzie. Image designed by Michael MacKenzie from an herbarium Specimen courtesy of the College of the Atlantic Herbarium, smartphone Screenshot of original data courtesy of fulcrum app, and a photograph of the Harvard boys in 1880 courtesy of the Northeast Harbor Library.

Start with the plant sex: a pattern of earlier springs has been documented as dates of flowering creep ahead in the calendar across the globe. However, at the species level, and even within populations, there is a lot of variability. Some plants have been observed blooming much earlier with warming spring temperatures, while others show no significant change. The timing of flowering — the technical term is ‘phenology’ — has the potential to impact plant-pollinator interactions, reproductive success, and competition. These tend to be important factors in conservation and management, but years of data are needed to detect phenological shifts.

If you’ve ever thought that botany doesn’t involve enough time travel, you are not alone. Plant ecologists studying climate change and flowering phenology are constantly wondering ‘is this happening when it used to happen?’ My job would be infinitely easier if I had access to a time machine. Instead, I have herbarium specimens, field notes, and journals; I have a lady with an amateur botanist streak and a troupe of Harvard boys who spent their summers cataloguing the natural history of Mount Desert Island in the 1880s. Mining these resources for historical ecological information often involves looking for data that they didn’t know they were collecting at the time. It’s cheesy, but true: in phenology, timing is everything.

More about phenology from NEON’s Project Budburst.