Changing climate, changing landscape: monitoring the vast wilderness of interior Alaska

Listen: stream or download the Field Talk interview with National Park Service ecologist Carl Roland on ESA’s podcast page, or on iTunes.

by Liza Lester, ESA communications officer

Broadleaf trees and tamarack burn gold with fall color against the ever-green of conifers in the northeast corner of Denali National Park & Preserve. The low (relative to the core of the Alaska Range, which includes Denali, the highest mountain in North America) Teklanika Hills loom in the background. In the foreground, the Teklanika River flows northeastward into the Tanana River drainage, a major tributary of the mighty Yukon River. Credit, Tim Rains, Denali National Park and Preserve, 2011.

“The current landscape is a mosaic, and it has different attributes, and it’s likely that whatever change happens is going to result in a mosaic as well, not this idea of [complete] replacement of conifer to broadleaf. And I think most people in the field fully understand that and accept it, but I think in the public debate, and [in] some simplification, it gets this idea in people’s heads like, you know, they’re going to look out the window and it’s going to be aspen parkland in 20 years. I just think that’s not going to happen.” – Carl Roland, 14 Feb 2013.

IN the polar regions, climate change is not hypothetical. Alaska is already feeling the consequences of a changing climate in melting permafrost, eroding coastlines, and retreating sea ice. National Park Service ecologist Carl Roland has seen unusual insect outbreaks and forest fires in recent years that may be harbingers of things to come – or may not. Predicting the future of landscape-scale change is not simple, not when you’re talking about landscapes as large and varied as the Alaskan Interior. Extrapolating from personal experience is risky. If we are to predict the future, Roland says, we need a benchmark against which to measure change in Alaskan forests. We need to know in some detail what is out there now.

In the February issue ESA’s journal Ecological Monographs, Carl and colleagues in the National Park Service’s Inventory and Monitoring program report on the first decade of ongoing ecosystem monitoring in Denali National Park. This particular report focuses on the trees, but the larger monitoring effort aims to sample vegetation more comprehensively.

Carl Roland (left) and Peter Nelson collect plant cover data near Kankone Peak in the Kantishna Hills in July, 2006. Credit, Alaska National Park Service.

Interior Alaska is snowy, but dry. The cold slows the departure of water after it lands, keeping the landscape wetter than more southerly locations, like Arizona, that get similar amounts of precipitation. Annual average temperatures have increased by 1.9C (3.42F) in Alaska since the 1960s, and much of the warming has happened in winter. Warmer winters may mean dryer summers, more fires, and a transition from the dominant spruce confers to broadleaf quaking aspen and balsam poplar, or even to grassland. Or they may not. Maybe Alaska will be wetter.

It could all come down to precipitation – and aspect, altitude, location. Alaska is a big place, encompassing wet maritime forests on the southern coasts, and continental grasslands towards Canada in the east. Denali National Park rises from lowland basins of the distinctive braided rivers as low as 73 meters (240 feet), to high alpine ridges, peaking at Denali’s (aka Mount McKinley’s) impressive 6,196 m (20,328 ft).

Last summer, Carl had teams in three National Parks, collecting data and samples in 10-day excursions scheduled back to back to back. The teams catalog species, measure trees and collect cores for tree ring analysis. They sample soil, record elevation, slope steepness and aspect, evidence of past fire and flood, and the presence or absence of permafrost. They estimate the amount of sunlight that graces the sample plot. They record 19 different environmental variables with the potential to influence the vegetation (and the animal life too).

Carl designed the monitoring study to assess what exists on the landscape now – which trees grow where, how densely, and in what abundance – and set a baseline that would be useful to as broad a cross-section of ecologists as possible. He wanted it to be applicable to many different types of questions, and hypotheses not yet imagined. It was not deliberately tailored to specific questions, although the Denali paper calls out four prominent visions of the future of forests interior Alaska: 1) fire-driven replacement of spruce and tamarack forests by broadleaf trees 2) the mass death of black spruce and white spruce from drought 3) spread of white spruce beyond contemporary tree-lines, up mountains and out into tundra 4) ravaging outbreaks of tree-eating insects.

The data tell Carl that conifers dominate the forests of Denali. He doesn’t see evidence of a major broadleaf insurgency – not yet. He emphasizes that this may yet happen. But for now, the spruce are still ascendant. White spruce thrives in soils free of permafrost, and on (relatively) warm, south-facing slopes. It’s struggling in some of its denser established enclaves, but shows potential to colonize currently tree-less lands given warmer seasons and retreating permafrost. Black spruce, which has the edge in colder, icier terrain, may be the species most at risk.

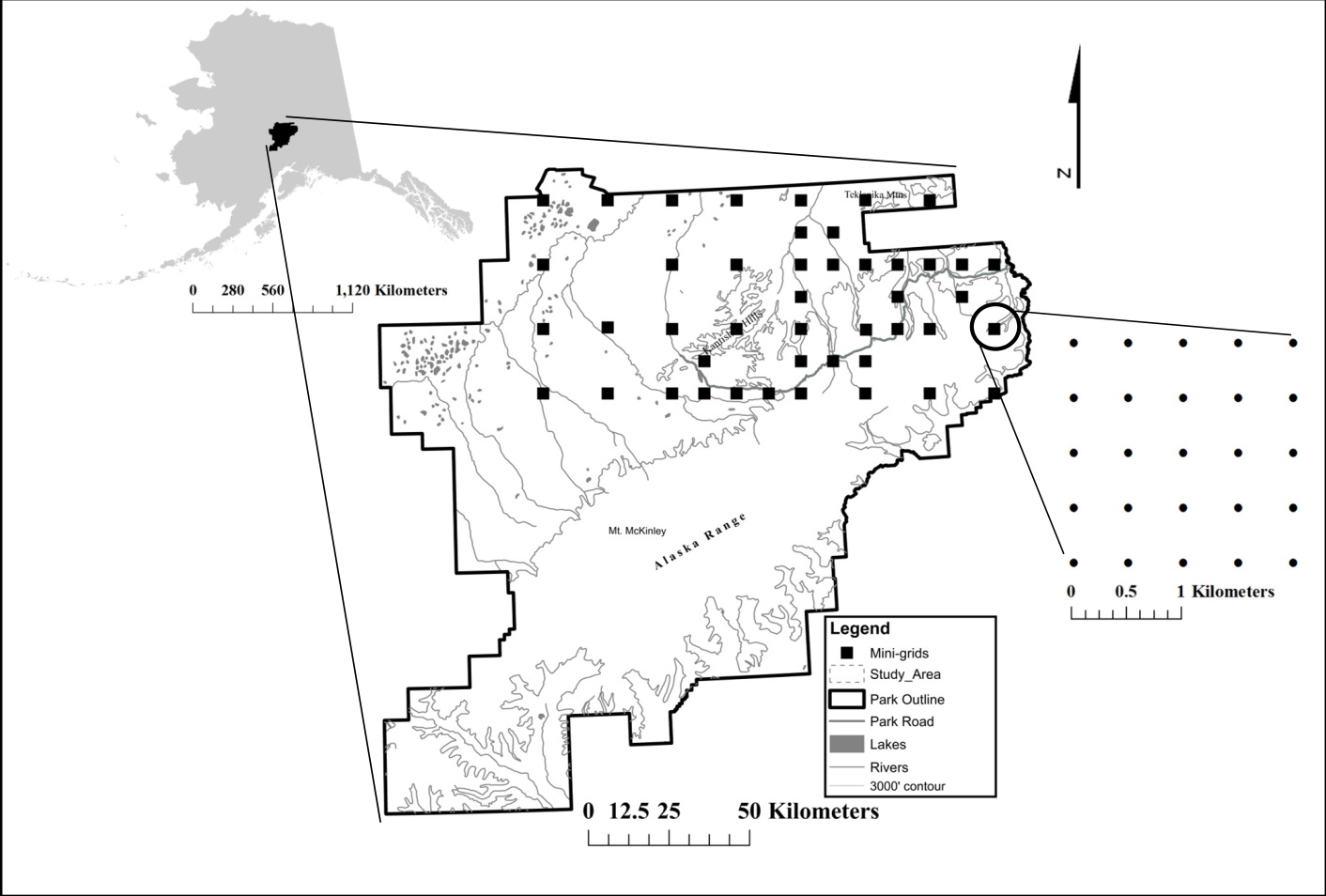

Sampling sites spread in a grid of 20km intervals over 12,800 km2 of the north end of Denali National Park, with supplementary sites clustered along the single, mostly unpaved, 148km road entering the park. Each square marks a 5 x 5 “mini-grid” of 25 sample plots at 500m intervals. From Figure 1 of the paper. Click to zoom.

- Want to see more photos of Denali? Check out DenaliNPS’s flickr collections of Landscapes and Monitoring vegetation in Denali National Park.

- NPS Inventory & Monitoring’s nationwide Vegetation Inventory Map.

- Access the data from this paper from Ecological Archives M083-001-S1.

![]() Roland, C., Schmidt, J., & Nicklen, E. (2013). Landscape-scale patterns in tree occupancy and abundance in subarctic Alaska. Ecological Monographs, 83 (01), 19-48 DOI: 10.1890/11-2136.1

Roland, C., Schmidt, J., & Nicklen, E. (2013). Landscape-scale patterns in tree occupancy and abundance in subarctic Alaska. Ecological Monographs, 83 (01), 19-48 DOI: 10.1890/11-2136.1